- Special Report

A Guide to Children Arriving at the Border: Laws, Policies and Responses

Published

Preface

The American Immigration Council is updating this Guide which was first issued in summer 2014. It provides information about the tens of thousands of children—some travelling with their parents and others alone—who have fled their homes in Central America and arrived at our southern border. This Guide seeks to explain the basics. Who are these children and why are they coming? What basic protections does the law afford them? What happens to the children once they are in U.S. custody? What have the U.S. and other governments done in response? What additional responses have advocates and legislators proposed? The answers to these questions are critical to assessing the U.S. government’s responses and understanding the ongoing debate about whether reforms to the immigration laws and policies involving children are needed.

Background: Who are the children, why are they coming, and what obligations do we have?

What does “unaccompanied children” mean?

Children who arrive in the United States alone or who are required to appear in immigration court on their own often are referred to as unaccompanied children or unaccompanied minors. “Unaccompanied alien child” (UAC) is a technical term defined by law as a child who “(A) has no lawful immigration status in the United States; (B) has not attained 18 years of age; and (C) with respect to whom—(i) there is no parent or legal guardian in the United States; or (ii) no parent or legal guardian in the United States is available to provide care and physical custody.” Due to their vulnerability, these young migrants receive certain protections under U.S. law. The immigration laws do not define the term “accompanied” children, but children arriving in the United States with a parent or guardian are considered accompanied.

Where are these children and families coming from?

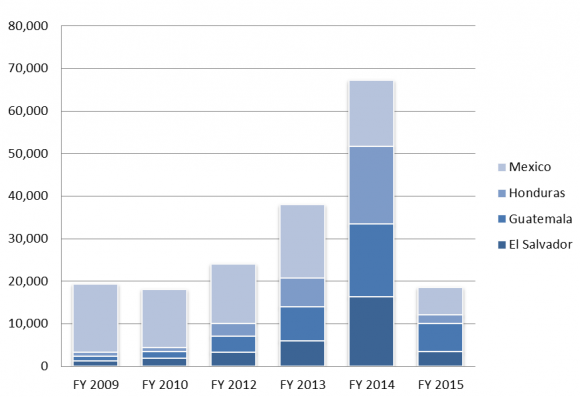

The vast majority of unaccompanied children and families arriving at the southwest border come from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, although unaccompanied children may arrive from any country. Over the past few years, increasing numbers of children and families have been fleeing violence in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador—a region of Central America known as the “Northern Triangle.” According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), a component of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), between October 1, 2013 and September 30, 2014, CBP encountered 67,339 unaccompanied children. The largest number of children (27 percent of the total) came from Honduras, followed by Guatemala (25 percent), El Salvador (24 percent), and Mexico (23 percent). The number of unaccompanied children arriving at the southern border has decreased since its peak in the summer and fall of 2014. Between October 1, 2014 and April 30, 2015, CBP apprehended 3,514 unaccompanied minors from El Salvador, 6,607 from Guatemala, 1,977 from Honduras, and 6,519 from Mexico. This represents approximately a 45 percent decrease from the same time period the prior year. The apprehensions of “family units” (children with a parent or legal guardian) also declined. There were 16,997 family unit apprehensions from October 1, 2014 to April 30, 2015, a 35 percent decrease from 26,341 apprehensions during the same time frame the year before. As discussed below, this decrease in apprehensions likely is tied to increases in apprehensions in Mexico and increased security measures along Mexico’s southern border.

Unaccompanied Migrant Children Encountered FY 2009-FY 2015*

Source: CBP.

*FY 2015 through April 30, 2015.

Why are children and families leaving their home countries?

Researchers consistently cite increased Northern Triangle violence as the primary motivation for recent migration, while identifying additional causes including poverty and family reunification. A report by the Assessment Capacities Project (ACAPS), citing 2012 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) data, highlighted that Honduras had a homicide rate of 90.4 per 100,000 people. El Salvador and Guatemala had homicide rates of 41.2 and 39.9, respectively. A 2014 analysis conducted by Tom Wong, a University of California-San Diego political science professor, took the UNDOC data and compared it to the data on unaccompanied children provided by CBP. Wong found a positive relationship between violence and the flow of children: “meaning that higher rates of homicide in countries such as Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala are related to greater numbers of children fleeing to the United States.”

While a child may have multiple reasons for leaving his or her country, children from the Northern Triangle consistently cite gang or cartel violence as a primary motivation for fleeing. Research conducted in El Salvador on child migrants who were returned from Mexico found that 60 percent listed crime, gang threats, and insecurity as a reason for leaving. In a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) survey of 404 unaccompanied children from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico, 48 percent of the children “shared experiences of how they had been personally affected by the…violence in the region by organized armed criminal actors, including drug cartels and gangs or by State actors.” Furthermore, the violence frequently targets youth. Recruitment for gangs begins in adolescence—or younger—and there are incidents of youth being beaten by police who suspected them of gang membership.

Are children coming to the United States because of DACA?

No. U.S. immigration enforcement policy, including deferred action programs that would allow certain undocumented immigrants to remain in the United States temporarily, is not a primary cause of the migration. Notably, the rise in violence and corresponding increase in unaccompanied child arrivals precede both the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and Senate passage of an immigration reform bill S.744—positive developments that are sometimes cited as pull factors by Obama Administration critics. In fact, in its 2012 report, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) stated that “in a five month period between March and July 2012, the UAC program received almost 7,200 referrals – surpassing FY2011’s total annual referrals,” showing that the rise in UACs predated the implementation of the DACA program. Furthermore, individuals who arrived in the country after January 1, 2007 would not be eligible for DACA.

Would more Border Patrol resources deter border crossers?

There is little evidence to support the proposition that the border must be further fortified to deter an influx of children and families. Treating the current situation as simply another wave of unauthorized immigration misses the broader policy and humanitarian concerns driving these children and families’ migration. In fact, many women and children are turning themselves over to Border Patrol agents upon arrival and are not seeking to evade apprehension.

Furthermore, CBP’s resources along the southwest border are already significant. There were 18,156 Border Patrol agents stationed along the southwest border as of Fiscal Year (FY) 2014. The annual Border Patrol budget stood at$3.6 billion in FY 2014. The Border Patrol has at its command a wide array of surveillance technologies: ground radar, cameras, motion detectors, thermal imaging sensors, stadium lighting, helicopters, and unmanned aerial vehicles.

What are our obligations under international law?

The United States has entered into treaties with other countries to ensure the protection and safe passage of refugees. Among the most important are the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol. Under these treaties, the United States may not return an individual to a country where he or she faces persecution from a government or a group the government is unable or unwilling to control based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. A separate treaty, known as the Convention Against Torture, prohibits the return of people to a country where there are substantial grounds to believe they may be tortured.

The United States has implemented these treaties in various laws and regulations. They form the basis for both our refugee program and asylum program. (An asylee is simply a refugee whose case is determined in the United States, rather than outside it.) In fact, under our laws, anyone in the United States may seek asylum, with some exceptions, or protection from torture with no exceptions. It can be difficult and complicated to determine whether an individual has a valid claim for asylum or protection from torture. To meet its protection obligations, the United States should ensure that children are safe, have an understanding of their situation and their rights, and have adequate representation when they tell their stories to a judge.

Do Central American children qualify for protections under international and U.S. law?

Many of the children fleeing to the United States have international protection needs and could be eligible for humanitarian relief. According to UNHCR’s survey of 404 unaccompanied children from Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, 58 percent “were forcibly displaced because they suffered or faced harms that indicated a potential or actual need for international protection.” Notably, of those surveyed, UNHCR thought 72 percent of the children from El Salvador, 57 percent from Honduras, and 38 percent from Guatemala could merit protection. While international protection standards are in some cases broader than current U.S. laws, the fact that over 50 percent of the children UNHCR surveyed might qualify as refugees suggests that a thorough and fair review of these children’s claims is necessary to prevent them from being returned to danger.

Moreover, children may qualify for particular U.S. forms of humanitarian relief for victims of trafficking and crime, or for children who have been abused or abandoned by a parent. A 2010 survey conducted by the Vera Institute of Justice indicated that 40 percent of children screened while in government custody could be eligible for relief from removal under U.S. laws. Given their age, the complexity of their claims, and the trauma that generally accompanies their journey, determining whether these children qualify for some form of protection can be a time-consuming process.

What types of U.S. immigration relief do children potentially qualify for?

The most common types of U.S. immigration relief for which children potentially are eligible include:

- Asylum: Asylum is a form of international protection granted to refugees who are present in the United States. In order to qualify for asylum, a person must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution based on one of five grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

- Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS): SIJS is a humanitarian form of relief available to noncitizen minors who were abused, neglected, or abandoned by one or both parents. To be eligible for SIJS, a child must be under 21, unmarried, and the subject of certain dependency orders issued by a juvenile court.

- U visas: A U visa is available to victims of certain crimes. To be eligible, the person must have suffered substantial physical or mental abuse and have cooperated with law enforcement in the investigation or prosecution of the crime.

- T visas: A T visa is available to individuals who have been victims of a severe form of trafficking. To be eligible, the person must demonstrate that he or she would suffer extreme hardship involving unusual or severe harm if removed from the United States.

What is the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA)?

The original Trafficking Victims Protection Act was signed into law in 2000 to address human trafficking concerns. It was subsequently reauthorized during both the Bush and Obama Administrations in 2003, 2005, 2008, and 2013.

The TVPRA of 2008, signed by President Bush, responded to concerns that unaccompanied children apprehended by the Border Patrol “were not being adequately screened” for eligibility for protection or relief in the United States. The TVPRA also directed the development of procedures to ensure that if unaccompanied children are deported, they are safely repatriated. At the outset, unaccompanied children must be screened as potential victims of human trafficking. However, as described further below, procedural protections for children are different for children from contiguous countries (i.e., Mexico and Canada) and non-contiguous countries (all others). While children from non-contiguous countries are transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for trafficking screening, and placed into formal immigration court removal proceedings, Mexican and Canadian children are screened by CBP for trafficking and, if no signs of trafficking or fear of persecution are reported, may be summarily returned home pursuant to negotiated repatriation agreements. The TVPRA in 2008 also ensured that unaccompanied alien children are exempt from certain limitations on asylum (e.g., a one-year filing deadline). It also required HHS to ensure “to the greatest extent practicable” that unaccompanied children in HHS custody have counsel, as described further below—not only “to represent them in legal proceedings,” but to “protect them from mistreatment, exploitation, and trafficking.”

Can new arrivals obtain a grant of Temporary Protected Status?

Although Salvadorans and Guatemalans in the United States have been eligible for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in the past, there currently is no category that would include children or families arriving today or at any point since the spring of 2014. TPS is a limited immigration status that allows an individual to remain temporarily in the United States because of civil war, natural disasters, or other emergency situations that make it difficult for a country to successfully reintegrate people. TPS requires a formal designation by the Secretary of Homeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State, and requires, among other things, that a country formally request this designation from the U.S. government.

How have other countries in the region responded to the increase in child migrants?

Mexico, with support from the United States, has responded to the increasing number of children and families fleeing Central America by expanding its security measures along its southern border as well as its internal enforcement. Part of the Mexican government’s southern border security plan is funded through the Mérida Initiative and as of October 2014, about $1.3 billion dollars in U.S. assistance went to Mexico through this initiative.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, migrants report an “increased presence of immigration officials in pickup trucks patrolling the roads and bus stations en route to the train line. Raids on hotels and restaurants where migrants shelter in traditional cities [i.e., cities along previously established migrant routes] have occurred. And immigration agents, in raids supported by federal police and the military, are targeting the trains, removing migrants from the train cars and detaining them. The companies that run the cargo trains on whose roofs migrants travel (referred to as “La Bestia”) also are working with the Mexican government to increase train speed in order to prevent migrants from riding on them.

Deportations from Mexico to the Northern Triangle countries increased significantly over the course of 2014, and this trend has continued into 2015. Mexico apprehended more than 15,795 minors between January and August of 2014, compared to 9,727 minors for all of 2013. According to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Mexican government, Mexico deported 3,819 unaccompanied minors from Central America during the first five months of FY 2015 – a 56% increase over the same period from FY 2014.

A report by the Human Rights Institute at Georgetown Law School found that while “Mexican officials are supposed to screen unaccompanied children for international protection needs, they often fail to meet this responsibility.” The report also found that the detention conditions deterred children from accessing the asylum process and that the Mexican government is failing to consistently inform children of their rights or screen them for international protection eligibility. Without these practices, the report argued, “current practices place a burden on migrant children to investigate the law and procedures and affirmatively apply for asylum.”

What is in-country processing?

In November 2014, the U.S. Department of State announced the launch of its in-country refugee processing program in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The program is intended “to provide a safe, legal, and orderly alternative to the dangerous journey that some children are currently undertaking to the United States.” The new program allows parents from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras who are lawfully present in the United States to submit an application to have their children join them in the United States if they qualify for refugee status or humanitarian parole.

Parents may submit applications for this program to the State Department. Once the application is submitted, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) will work with the child in country and invite them to pre-screening interviews. Both the child and the parent will have to submit to DNA testing to ensure the biological relationship, and DHS will conduct an interview for refugee eligibility. As with all refugees, the children will have to submit to and pass security checks to be eligible for refugee status. If they do not qualify for refugee status, it is possible that they may qualify for humanitarian parole on a case-by-case basis. Although humanitarian parole permits a person to travel safely to the United Sates to reunite with a parent, unlike refugee status, it does not provide a path to citizenship.

While this program will help some eligible children and their parents, its impact is expected to be limited. Any refugees admitted under this program would count against the current limit of 4,000 refugee admissions for Latin America and the Caribbean. In contrast, 68,541 children crossed the border in FY 2014. The program itself is rigorous, and its requirements—a parent with legal status and DNA and security checks—will limit who qualifies. Eleanor Acer of Human Rights First argued that “[p]ractically speaking, the program will need to actually extend protection in a timely manner to a meaningful number of applicants if it is to be viewed as a credible alternative to some families with at-risk children.” Additionally, Acer note that in the past, U.S. officers have used “the existence of in-country resettlement…to limit access to protection.”

Procedures and Policies: What happens to children and families when they arrive at the border?

How are unaccompanied children treated compared to adults and children arriving in families?

How a noncitizen is treated upon apprehension depends on where the person is apprehended (near the border or in the interior), what country he or she is from (a contiguous country or a noncontiguous country), and whether he or she is an unaccompanied minor.

Adults and families, when apprehended in the interior, typically are placed in removal proceedings before an immigration judge. However, that is not necessarily the case for adults or families apprehended at or near the border. In FY 2013, 83 percent of adults removed by the U.S. were deported through summary, out-of-court removal proceedings by a DHS officer rather than appearing before an immigration judge. The most common summary removal processes are expedited removal, used when a noncitizen encounters immigration authorities at or within 100 miles of a U.S. border with insufficient or fraudulent documents, and reinstatement of removal, used when a noncitizen unlawfully reenters after a prior removal order.

As discussed in detail below, unaccompanied children receive greater protections under U.S. law.

What happens to unaccompanied children once they are in U.S. custody?

The majority of unaccompanied children encountered at the border are apprehended, processed, and initially detained by CBP. Unlike adults or families, though, unaccompanied children cannot be placed into expedited removal proceedings.

Children from non-contiguous countries, such as El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras, are placed into standard removal proceedings in immigration court. CBP must transfer custody of these children to Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), within 72 hours, as described below.

Each child from a contiguous country—Mexico or Canada—must be screened by a CBP officer to determine if he or she is unable to make independent decisions, is a victim of trafficking, or fears persecution in his home country. If none of these conditions apply, CBP will immediately send the child back to Mexico or Canada through a process called “voluntary return.” Return occurs pursuant to agreements with Mexico and Canada to manage the repatriation process.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have expressed concern that CBP is the “wrong agency” to screen children for signs of trauma, abuse, or persecution. The public justice group Appleseed issued a report that stated, “as a practical matter” CBP screening “translates into less searching inquiries regarding any danger they are in and what legal rights they may have.” Appleseed also expressed concern that the U.S.-Mexico repatriation agreement has been geared towards “protocols of repatriations logistics,” rather than best practices for child welfare.

Do children get attorneys?

In general, children facing deportation—just like adults facing deportation—are not provided government-appointed counsel to represent them in immigration court. Under the immigration laws, all persons have the “privilege” of being represented “at no expense to the Government.” This means that only those individuals who can afford a private lawyer or those who are able to find pro bono counsel to represent them free of charge are represented in immigration court. And, although Congress has directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to ensure the provision of counsel to unaccompanied children “to the greatest extent practicable,” Congress further explained that the Secretary “shall make every effort to utilize the services of pro bono counsel who agree to provide representation to such children without charge.”

A vast network of pro bono legal service providers has responded to the call, and during the past year, the Obama Administration provided some funding to legal service providers in order to increase representation for unaccompanied children. The justice AmeriCorps program, announced in June 2014, awarded $1.8 million for representation of certain children in immigration court, and HHS subsequently provided an additional $9 million for representation in FY 2014 and FY 2015.

But while pro bono legal service providers represent many children nationwide, they still are unable to meet the need. As of April 2015, children in over 38,000 pending cases remained unrepresented. These children are forced to appear before an immigration judge and navigate the immigration court process, including putting on a legal defense, without any legal representation. In contrast, DHS, which acts as the prosecutor in immigration court and argues for the child’s deportation, is represented in every case by a lawyer trained in immigration law. As a result, advocates, including the American Immigration Council, filed a nationwide class-action lawsuit challenging the federal government's failure to provide children with legal representation in immigration court. The case, JEFM v. Holder, is currently pending before a federal district court in Washington State.

How have immigration courts responded to the increased volume of cases?

In the summer of 2014, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), the division within the Department of Justice which houses the immigration courts, adopted a new policy with respect to prioritizing cases for adjudication. The stated goal of this new policy was to “[f]ocus the department’s immigration processing resources on recent border crossers” (i.e., individuals who arrived on or after May 1, 2014). Under the policy, the immigration courts are to prioritize the following cases: (1) unaccompanied children who recently crossed the southwest border; (2) families who recently crossed the border and are held in detention; (3) families who recently crossed the border but are on “alternatives to detention” and (4) other detained cases. Immigration courts now schedule a first hearing for unaccompanied children within 21 days of the court’s receiving the case. Given the speed at which these cases progress, the expedited children’s dockets often are referred to as “rocket dockets.” Children on the rocket dockets may be provided with less time to find attorneys before immigration courts move forward with their cases—and, as a result, may be required to explain why they should not be deported without the help of an attorney. If they are unable to do so, unrepresented children may be ordered removed or required to “voluntarily” depart from the United States.

Can unaccompanied children be detained?

Yes, but special laws govern the custody of children based on child welfare standards that take the “best interests” of the child into account. Unaccompanied children must be transferred by DHS to the custody of HHS within 72 hours of apprehension, under the Homeland Security Act of 2002 and TVPRA of 2008. HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) then manages custody and care of the children until they can be released to family members or other individuals or organizations while their court proceedings go forward.

Under the TVPRA of 2008, HHS is required to “promptly place” each child in its custody “in the least restrictive setting that is in the best interests of the child.” As such, children in ORR care are generally housed through a network of state-licensed, ORR-funded care providers, who are tasked with providing educational, health, and case management services to the children.

Under international law, children “should in principle not be detained at all,” according to UNHCR. Detention, if used, should only be a “measure of last resort” for the “shortest appropriate period of time,” with an overall “ethic of care.” Detention has “well-documented” negative effects on children’s mental and physical development, including severe harm such as anxiety, depression, or long-term cognitive damage, especially when it is indefinite in nature.

Children who arrive with a parent may be detained by DHS in family detention centers, described below.

Can unaccompanied children be released from custody?

Yes. ORR seeks to reunify children with family members or release them to other individual or organizational sponsors whenever possible, on the grounds that children’s best interests are served by living in a family setting. ORR also is required to ensure that individuals taking custody of the children are able to provide for their well-being. Federal regulations, following a court settlement in the case Flores v. Reno, outline the following preferences for sponsors: (1) a parent; (2) a legal guardian; (3) an adult relative; (4) an adult individual or entity designated by the child’s parent or legal guardian; (5) a licensed program willing to accept legal custody; or (6) an adult or entity approved by ORR. The sponsor must agree to ensure that the child attends immigration court.

As of May 2014, ORR reported that the average length of stay in its facilities was approximately 35 days and that about 85 percent of the children served are released while their deportation proceedings are in progress.

Does the Government detain families?

Yes. The increase in families fleeing violence and arriving at the southwest border—frequently mothers with children—has reignited a debate over the appropriate treatment of families in the immigration system. Family immigration detention has a complicated and troubled history in the U.S.

Prior to 2006, ICE commonly detained parents and children separately. In FY 2006 appropriations language, however, Congress directed ICE to either “release families,” use “alternatives to detention such as the Intensive Supervised Appearance Program,” or, if necessary, use “appropriate” detention space to house families together. ICE responded by opening the T. Don Hutto Residential Center in Texas, with over 500 beds for families. But, as the Women’s Refugee Commission explained, the “Residential Center” was a “former criminal facility that still look[ed] and [felt] like a prison.” The Hutto detention center became the subject of a lawsuit, a human rights investigation, multiple national and international media reports, and a national campaign to end family detention. In 2009, ICE ended the use of family detention at Hutto, withdrew plans for three new family detention centers, and said that detention would be used more “thoughtfully and humanely.”

Yet, in the summer of 2014, in response to the increase in families fleeing violence and arriving at the southwest border, the federal government established a makeshift detention center on the grounds of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Artesia, New Mexico, a remote location more than three hours’ drive from the nearest major city. According to the DHS Secretary, the detention and prompt removal of families was intended to deter others from coming to the United States.

Over the course of the summer and fall 2014, over hundreds of women and children were detained in Artesia. The facility was ultimately closed several months later, but the government has continued its policy of detaining women and children. Currently families are housed in three facilities: the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, Karnes County Residential Center in Karnes City, Texas, and Berks Family Residential Center in Leesport, Pennsylvania. Both the Dilley and Karnes facilities are owned and operated by private prison companies. By the end of May 2015, Dilley’s capacity will be 2,400, making it by far the largest family detention center in the United States.

Family detention is rarely in the “best interests of the child,” as opposed to community-based alternatives. Detaining children leads to serious mental health problems and chronic illnesses, and detaining families can have long-lasting effects on the psychological well-being of both parents and children.

In 2014 and 2015, several detained families filed lawsuits to challenge various aspects of family detention. One case challenges the government’s policy of detaining families as a means to deter others from coming to the United States. In this case, RILR v. Johnson, a federal court issued a preliminary injunction to prevent the government from using deterrence as a factor in making a bond determination. In a second case, lawyers for children held in family detention facilities have claimed that the government is violating the terms of the settlement agreement inFlores, discussed above. This settlement established national standards for the detention, release and treatment of children detained by DHS for deportation.

Can alternatives to detention be used for families?

Yes. ICE operates two alternatives to detention (ATD) programs for adult detainees—a “full service” program with case management, supervision, and monitoring (either by GPS or telephone check-in), and a “technology-only” program with monitoring only. According to U.S. government data, 95 percent of participants in ICE’s full service program appeared at scheduled court hearings from fiscal years 2011 to 2013. Further, in FY 2012 only 4 percent were arrested by another law enforcement agency. ICE’s alternatives program, as well as being more humane, is also less expensive than detention—$10.55/day as opposed to $158/day. As to asylum seekers, a prior U.S. government-commissioned study found that “asylum seekers do not need to be detained to appear,” and “[t]hey also do not seem to need intensive supervision.” Bipartisan support has emerged for alternatives to immigration detention. ICE, in early 2015, issued requests for proposals for “family case management services” for up to 300 families apiece in Baltimore/Washington, NYC/Newark, Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles.

U.S. Government Response and Proposed Solutions

During the summer of 2014, the Obama Administration’s response to Central American children and families arriving in the U.S. focused largely on enforcement measures, rather than humanitarian measures that had previously received legislative support, and would have been more tailored towards the vulnerable arriving population.

The Administration requested significant funding to support an “aggressive deterrence strategy” and implemented family detention and “rocket dockets” for children and families. Its in-country refugee processing program has been expected to assist relatively few people. Congressional legislative proposals, at the time and since, have largely focused on rolling back procedural protections for children. That said, proposals also exist to more holistically protect children and families reaching the United States, several of which passed the Senate in 2013 as part of its comprehensive immigration reform bill.

U.S. Government Response—Administration’s and Congress’ Actions

The following table summarizes the Administration’s and Congress’ major actions since summer 2014:

|

Date |

Who |

Action Taken |

|---|---|---|

|

June 2, 2014 |

President Obama |

Declared “urgent humanitarian situation” and directed a coordinated federal response under emergency homeland security authorities. |

|

June 20, 2014 |

DHS |

Announced intention to detain families at the Border Patrol training center in Artesia, NM. Detainees arrived in Artesia around the beginning of July. |

|

June 30, 2014 |

President Obama |

Sent letter to Congressional leaders declaring intent to seek emergency funding for “an aggressive deterrence strategy focused on the removal and repatriation of recent border crossers.” |

|

July 8, 2014 |

President Obama |

Sent letter to Speaker Boehner (attaching OMB analysis) requesting $3.7 billion in emergency appropriations. Request included:

|

|

July 9, 2014 |

DOJ-EOIR |

Immigration courts prioritized cases of recent border crossers who are unaccompanied children, families in detention, and families on alternatives to detention. |

|

July 11, 2014 |

DHS |

Modified contract with Karnes County, TX to detain families at ICE’s existing detention facility for adults there. |

|

July 31, 2014 |

Senate |

Bill to provide $2.7 billion in emergency appropriations failed in procedural vote. |

|

August 1, 2014 |

House of Representatives |

|

|

August 1, 2014 |

DHS |

|

|

September 22, 2014 |

DHS |

Agreed to pay town of Eloy, AZ to modify its existing agreement with ICE so that the private company CCA can build a new family detention facility in Dilley, TX. DHS publicly confirmed the opening of Dilley the next day. |

|

November 18, 2014 |

DHS |

Announced ICE will close the Artesia, NM family detention facility and transfer the detainees to the new Dilley, TX family detention facility. |

|

December 3, 2014 |

State Dep’t |

Launched in-country refugee processing program in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. |

|

December 16, 2014 |

Congress and President Obama |

FY 2015 “Cromnibus” appropriations bill, signed by President, provided:

|

|

February 2, 2015 |

President Obama and DHS |

The Administration’s request for DHS funding for FY 2016 included:

|

|

March 4, 2015 |

Congress and President Obama |

FY 2015 DHS Appropriations bill, signed by President, provided:

|

|

May 27 and June 1, 2015 |

House and Senate |

136 Representatives and 33 Senators wrote letters asking DHS Secretary Johnson to end family detention. |

Recent Legislative Proposals

Since the summer of 2014, most legislative proposals have focused on rolling back the procedural protections that the TVPRA affords to Central American unaccompanied children. For example, the House’s 2014 “Secure the Southwest Border Act” would have amended the TVPRA to (1) treat children from non-contiguous countries similarly to Mexican and Canadian children, but (2) strike the current requirement that the child be able to make an “independent decision to withdraw the child’s application for admission” before proceeding with voluntary return; (3) require those children who may have been trafficked or fear return [or require the remaining children] to appear before an immigration judge for a hearing within 14 days of screening; and (4) impose mandatory detention until that hearing.

Other proposals have offered variations on these themes. For example, the “Protection of Children Act of 2015,” which the House Judiciary Committee moved forward on March 4, 2015, would enact the above four changes—but additionally, expand from 72 hours to 30 days the time limit for CBP to transfer remaining unaccompanied children to HHS custody. That bill, among others, also proposes restricting HHS’ ability to provide counsel to unaccompanied children. Or, the “HUMANE Act,” sponsored by Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) and Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-TX) in 2014, would have gone further to place children with a fear of return into a new 7-day expedited process, during which the child would be required to prove her eligibility for immigration relief to an immigration judge while mandatorily detained, before moving on to a standard removal proceeding in immigration court.

Proposed Solutions

Before summer 2014, bipartisan support existed for legislative reforms to more holistically protect children and families reaching the United States. Since then, NGOs and advocacy groups have reiterated support for those reforms, as well as for aid to address root causes of child and family migration from Central America.

These reforms include:

- Incorporating a “best interests of the child” standard into all decision-making, not just custody decisions. Bipartisan immigration reform legislation which passed the Senate in 2013 (S. 744) would have required the Border Patrol, in making repatriation decisions, to give “due consideration” to the best interests of a child, “family unity,” and “humanitarian concerns.” Amendment 1340 to S. 744, which was not voted on as part of a compromise, would have made the best interests of a child the “primary consideration” in all federal decisions involving unaccompanied immigrant children. Organizations have also recommended adopting more child-specific procedures.

- Child welfare screening to replace or augment Border Patrol screening. Border Patrol agents are currently tasked with screening Mexican and Canadian children for trafficking and persecution and preventing their return to persecutors or abusers. NGOs have uniformly questioned Border Patrol’s ability to do so adequately, and reform proposals have ranged from improved training for CBP officers (included in S. 744), to pairing CBP screeners with child welfare experts (also in S. 744) or NGO representatives, to replacing CBP screeners with USCIS asylum officers. CBP Commissioner Kerlikowske recently expressed openness towards similar proposals.

- Due process protections and resources. NGOs have advocated for a system that provides procedural protections and resources to appropriately protect children and families from violence, under international and U.S. laws, without unduly delaying decision making. Proposals include appointed counsel, additional resources to legal orientation programs and additional resources to backlogged immigration courts (all included in S. 744). More recent proposals also include additional U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officers, and additional post-release caseworker services, to protect children, assist families, and ensure attendance at proceedings.

- Detention reforms. NGOs have proposed that children be detained as little as possible, released to families or other sponsors whenever appropriate, and if detained, supervised in a community-based setting because of detention’s severe impact on children. At least one Senator has promised legislation to end the detention of asylum-seeking families if no family member poses a threat to the public or a flight risk. Along these lines, organizations and legislators have recommended improving detention conditions, and expanding alternatives to detention (as S. 744 proposed), by reallocating detention funding to those cheaper alternatives.

- Aid to sending countries. NGOs have proposed aid to sending countries and Mexico, to invest in systems that protect and care for children, help youth live productive lives, and ultimately reduce violence and address root causes of flight. In January 2015, the White House announced it was seeking $1 billion in Central American assistance in its FY 2016 budget.